I went to tell my landlady that my bulb had burned out. It was 7:00am and she was in the kitchen cooking, while one of the Indian domestic helpers—a teenage girl—stirred several large pots on a roiling boil. My landlady, Da, is petite and wears her dark hair parted in the center and clasped in a low bun or ponytail, as is the custom of married Tibetan women. As I was about to leave she called out. “My husband is back from America and he speaks very good English. We would like to have you over for dinner.” She has this way of smiling and nodding while bowing her frame in an Asian sign of respect. I agreed to come the next evening at 6:30pm.

Up until this moment, I’d only spoken to her three times to pay the rent. I was staying in McLeodganj, India, volunteering as an English tutor. I realized in that moment why she and I had had sparse communication—she considered her English inferior to her husband’s, and had been too shy to engage me.

Who knows why, but I decided to show up to dinner wearing long johns, and a hip-length sweater layered with a short down vest over it. Oh, and black socks with beige slippers. No really—I showed up for dinner looking like a Korean ahjumma who has completely thrown in the towel. All that was missing were kimchee stains on my hands and sleeves.

I knocked on the front door and a handsome Tibetan man welcomed me in. Tibetan men and women wearing beautiful traditional chupas and tunics filled the house. Hesitatingly, I asked if Da was around? “Yes”, the man replied. Da emerged from her bedroom dressed in a beautiful chupa.

“Uh, hi Da, were we having dinner tonight?”

“Yes,” she said smiling and nodding.

“Ok… who are all these people?”

“Oh, we’re having a wedding here and my husband is performing the ceremony now.”

Huh? A wedding? She never mentioned wedding—and did I mention I decided to wear long johns? Black socks with beige slippers!

“So,” and I started to back away, “why don’t I come back another time—”.

But she wouldn’t have it and grasped my one hand in both of hers and said, “No! We want you to stay. You stay. I made vegetarian bagleb for you.”

And that sealed my fate. I had forgotten that the majority of Tibetans eat meat, but I had been abstaining while in India. After seeing carcasses hanging around in doorways exposed to black car fumes, cigarette smoke, pelted with rain and hail—I decided to live off a steady diet of fried rice and Indian chaat. So with that, Da led me by the hand through the crowded dining room to the family room. She left me on the couch and disappeared into the kitchen.

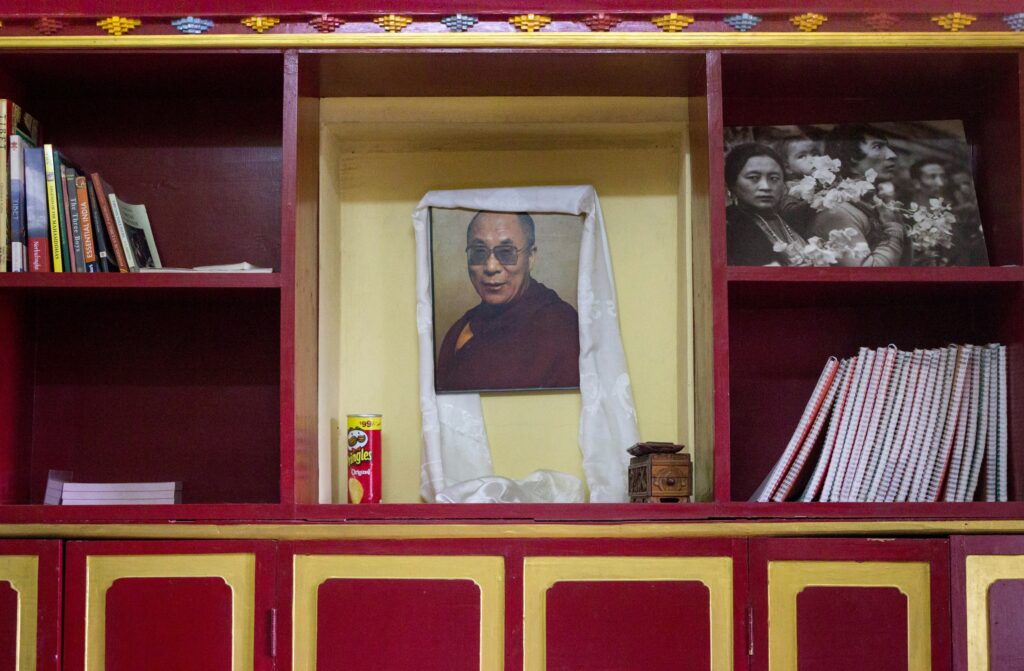

I looked around the room: an enormous TV surrounded by photos of the Dalai Lama, along with photos that reveal a tight-knit family and doting parents; two couches, an armoire, Tibetan and western artwork on the wall. It could have been the family room of an upper-middle class home in the US. There was an elderly man sitting hunched-over on the adjacent couch. He was the father of the groom. A couple of half-Tibetan kids and the six year old daughter of Da were playing with stuffed animals.

Their entire property is a three-story building, of which Da’s family occupies the top floor. The lower two stories make up individual rooms, a communal kitchen and bathroom. These are usually rented out to long term volunteers, but also to foreign and domestic tourists. Her teenage son lived in one of the rooms. One morning walking to the bathroom at 5:00am, I could see reflected in his window that he was watching the NBA. He kept his curtains closed, thus leaving his room in perpetual black-out. He smoked nearly nonstop and blasted his tunes—Backstreet Boys, Rihanna, Lil Wayne—a definite Americanophile. In typical teenage fashion, he did not come to the wedding.

Da swiftly lifted the curtain separating the family room from the kitchen and emerged like a cute, petite sargeant supervising pots on roiling boil. “Come!” she said, and I dutifully followed her back into the dining room. “Here,” she said, and heaped a bunch of kataks in my arms. I was so moved by her generosity! But I didn’t need so many, one katak was plenty! In an adjoining room, her husband was seated on an ornate chair performing the puja, while opposite sat the bride and groom. They were each swathed in satin and silk; the bride’s black hair held neatly in one braid down her back. The father of the groom was also there, seated on a fancy sofa. Da motioned for me to enter, and so I did, assuming everyone else was also coming inside. Nope, just me and these amazingly beautiful, traditionally outfitted Tibetans. The scene resembled an ancient ceremony with me as ahjumma-meme photoshopped in.

I was witnessing the ring exchange, and the rings in question were bright, yellow gold bands. Then, one-by-one, the women started to enter and drape a katak on Da’s husband; one each for the bride and groom, one for the father of the groom, and one on the bookcase. Ohh, I realized—the katak in my arms were for me to drape, not to keep! I was too self-conscious to stand up, so Da’s husband motioned and a woman came in and showed me what to do. I draped one on the bride, then the groom, and said “Congratulations.” Then one for the father of the groom. I was led to the bookcase where there was a mound of katak’s on the handle. “Place one here,” I was told, “and then put your head to the glass to honor the mother of the Dalai Lama.” There was a framed portrait of an elderly woman inside the glass bookcase. I had assumed it was their grandmother. Thank God my ignorance remained inside.

“In Tibetan Buddhism, it is traditional to present a katak or kata as a sign of respectful greeting and as an offering to lamas after an empowerment or teaching. The katak symbolizes purity and compassion and is presented at many ceremonial occasions, including births, weddings, funerals, graduations, and arrival or departure of guests.”

The ring ceremony concluded, I was again led back to the family room and waited on the couch.

Da’s husband, Ka came and joined me shortly thereafter while the women got busy setting the table and putting out food. He is a lama, a title given to a Tibetan priest or teacher of the dharma. He had just returned from New Orleans where he had given a meditation retreat. New Orleans has a special relationship with both Ka and Tibetan Buddhism, even though there is no Tibetan temple or community there.

“Only one Tibetan man married to an American woman.” Students from Tulane University regularly come to Mcloedganj as part of an exchange program. Ka said his usual schedule had him traveling many times a year to the US and Europe.

I asked about Tibetan wedding customs. Ka said monks and nuns aren’t invited because it is believed their presence will bring infertility to the couple. But then Ka added, “Maybe they should be invited to weddings because kids are so expensive!” and he laughed. Then added, “The mother is stressed—she can’t afford daycare and therefore, can’t go to work.” It is true that a lot of volunteer opportunities in McLeodganj were for daycare.

Then I asked about the mood of Tibetan refugees. In the company of a well-to-do family, it is sometimes easy to forget they are refugees, for they do not fit the image portrayed in the media: hapless groups living elbow-to-elbow in tent cities. Yet there are constant reminders that Tibetan refugees want to establish rights of a citizen, to obtain legal and fair access to their homes and land, and they want a chance at the American Dream. Cue Ka informing me that on his most recent trip to the US, he had left his eldest daughter with his brother’s family in California so she could apply for political asylum. “All Tibetans want to go to America, but once there do not realize they can only get the lowest jobs.” It corresponded to my student who was trying to get a visa to join her fiancé in Washington DC. He is Tibetan and washes dishes in a sushi restaurant.

During our conversation, Ka repeatedly inquired about my comfort; did I want tea, was I warm enough (did he not notice the long johns?). Finally it was time to eat, and they had prepared a special vegetarian menu for me: pureed spinach soup, vegetarian chowmein, and vegetarian bagleb, which is a deep-fried pastry customarily filled with vegetables and meat. Ka served me first and told me to start eating. Hilariously, immediately upon finishing their plates, the women disappeared from the table and re-emerge in jeans and t-shirts! Some had on sneakers, and one wore comfy slippers.

This was a good time to make a gracious exit and I bid everyone good night. Lying in bed, I reflected on their wonderful hospitality, Da’s exceptional cooking skills, and how my I finally fit in at the end.

* * *

note: names have been abbreviated to preserve privacy

Leave a Reply