We found out that José has cancer.

It’s hemangiosarcoma, our veterinarian said. I don’t know if it’s the spread-really-aggressively kind or the spread-more-slowly kind.

C (my fiancé at the time) asked, How long does he have?

Anywhere from three months to one year, she replied.

C turned to our little altar on the mantle. Crying openly, he lit some incense and candles.

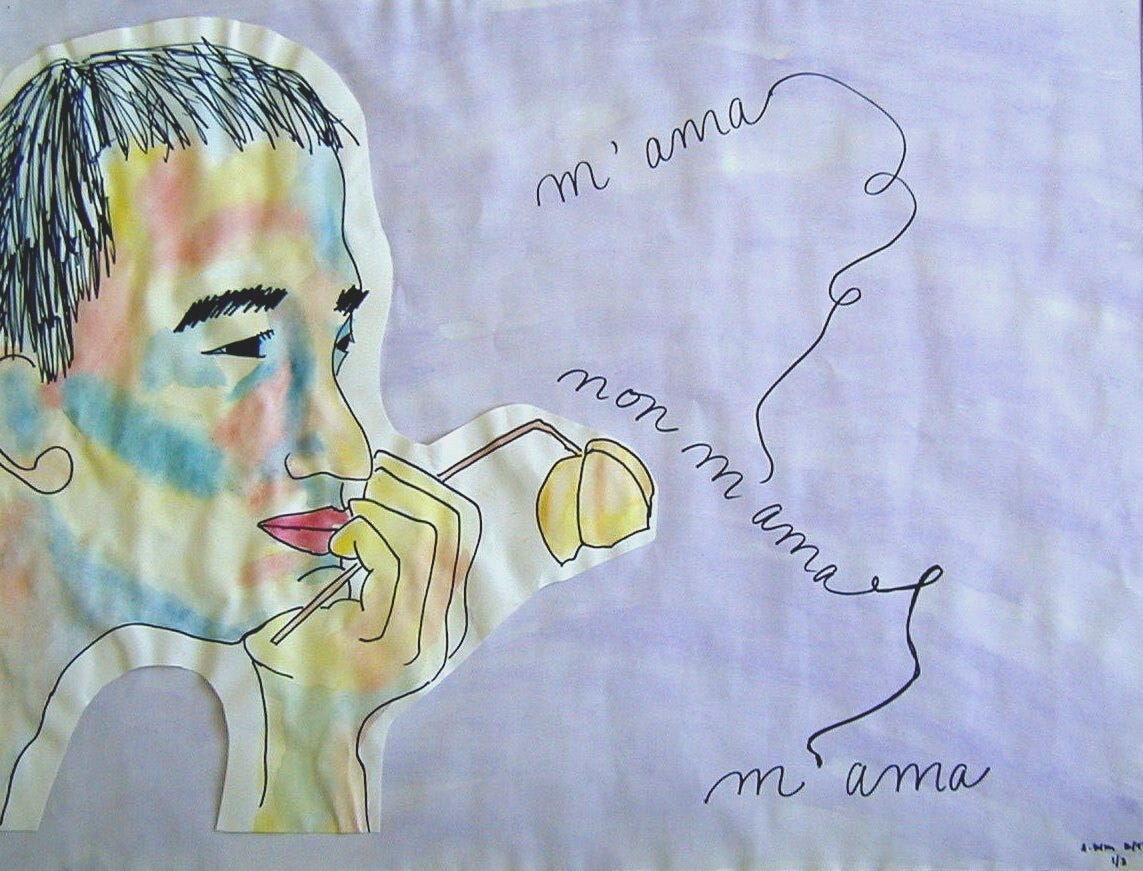

The way I heard it was, José has “mangia sarcola.” It sounded like an Italian entrée of glistening pasta and bits of lamb nestled on a bed of arugula, dressed with olive oil and garlic. It sounded like an Italian film star with pouty lips and pouty breasts, sounded like a Tuscan villa or a Ligurian winery.

But not cancer. No, mi amor, not that.

I look at José and visualize pasta and a leg of lamb growing inside him. Visualize dark purple grapes growing inside him. In the meantime, we light candles and burn incense.

Every night since José came home

from the hospital, he has to sleep with me. I moved to a twin-sized mattress in the living room—low to the ground because he can’t jump anymore. Earlier in his disease, he was able to jump up onto our tall sleigh bed. However, he no longer had the strength to jump down before we spotted him. Caught and culpable, he would wag his tail and cry pitifully in the center of our bed. I held his emaciated frame in my arms and wept all over his fur. I was the culpable one; I could not prevent his cancer.

I hear José’s pitter-patter and his gentle snorting to announce himself. I look up and see his handsome face looming above mine, his strong muzzle, his curly chest hair, his large droopy eyes, patiently waiting for me to invite him in. I scoot to the edge of the bed, pull back the covers and pat the mattress. Only then does he get up and curl into my belly. In return, I put my hand over his belly, over his growing pasta-lump. It’s inconceivable really, what to say, what to think.

I pet him, massage him. I pray. A lot.

Now I lay him down to sleep,

I pray the Lord his soul to keep,

If he should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord his soul to take.

Which is the dream, which is real?

Is it a dream that as I stood in the bathroom, it began to flood, the water rising and rising, up to my waist, up to my chest? Is it a dream that José could no longer swim and I saw his face go under— drowning—and I yanked him up, and swam with him on my back?

Is it a dream, or real, that when we went out for our morning walk, José began heading off in one direction, but upon seeing me standing at the top of the stairs, he trotted back to me with a smile on his face? Is it a dream that when I bent to pet him, he jerked his body back and forth, swooned, collapsed and began drooling onto the cement?

And is it a dream that in this slate-grey city, I knelt next to him and held his wet chin my hands. José, José, what’s going on? José—? I look into his eyes. Can you tell me anything? What is it? Pablo comes sprinting over thinking this is a game and barks in my face, squishes his nose into my pocket while I’m kneeling, stroking my drooling ten year old dog.

No Pablo. Sit down. Sit down. He paws me. NO. Lie down.

I’ve got two eighty-pound dogs lying on the ground and I’m telling myself, Don’t cry. Don’t cry here, not at the park, not at the top of the stairs. A lady in a sleeveless vest walks by and I make my face impassive. We’re just having a time-out, resting here.

Don’t cry. Don’t cry. Not yet.

Why not yet?

Crying. I don’t know how to let go. I don’t. I tell myself I do but I don’t. How to say, My dog just collapsed and he’s drooling and I don’t know what this means—any of it. I don’t know anything.

Let go.

What does that mean? Don’t take him to the hospital? Don’t try and prolong his life? Don’t authorize the chemo treatments?

What does it mean, let go? How do I do that?

You tell me. Tell me how to let go of my boy. Tell me, should I take him in and subject him to needles and radiation, to being restrained, to being locked up in a kennel with a poodle whose muzzle has been eaten through with acid as his neighbor?

Or keep him here at home with me, where he has a clean bed, where he watches me make his carrot juice? Yes, carrot juice. It’s what I would drink if I had cancer, and no one seems to be around at the moment to suggest otherwise.

No one seems to be around to tell me how to let go and so in the meantime, I juice. And so in the meantime, I live with this awareness that at any time, he could go. Any. Time. And in the meantime, he continues to crawl into bed with me every night and I say my prayers. I talk to him, tell him things. They differ from day to day. Today I said: You are more than your shell. You are beautiful and everlasting. Please don’t hang on for me, mi amor. I watch him stagger on stiff legs.

Mi amor, when you are no longer José, I bow my head, I will help you, help release you.

In the meantime I am too sharp with Pablo, yelling, shouting, hissing. He doesn’t understand why he can’t play with José, why he can’t tackle him and run into him. I don’t know what to tell him either, except, Drink your juice.

Yes, he gets carrot juice because José gets carrot juice.

Which is the dream, you tell me? Swimming through my bathroom with José on my back, or juicing for two golden retrievers?

Does it matter? They are the same to me.

Leave a Reply